William Nicholson Edgill was my 2x great grandfather. Born in Sheffield, Yorkshire in 1821, and the son of a mason, William was on his way upwards. My favourite discovery is a newspaper clipping that I found, that tells a lot about his character. I will share that clipping shortly, but first, let me tell you a little about this man.

William Nicholson Edgill was born around 1821 in Sheffield, to John Edgill and Hannah Nicholson. John was a mason, from Marylebone, Middlesex (now London). Sadly I don't know much about Hannah Nicholson; I've been unable to trace anything much about her life. John and Hannah married in Rotherham, Yorkshire. At some point after William's birth Hannah died, and John remarried a lady by the name of Frances. John and Frances had one daughter, by the name of Jane in 1827. The 1841 Census recorded the family of 4 as living at Castle Hill, Sheffield with John working as a mason, and Frances as a shopkeeper. William was also working, as a merchant's clerk, at the age of 20. It seems that the family were definitely of the lower middle class; all with paid employment and literate, but no live in servants to speak of. William was setting off in an upward trajectory.

|

| Castle Hill, Sheffield, circa 1900 |

In 1846 William married Elizabeth Hague, and in the following 4 years welcomed their first two children into the world; Tom Nicholson Edgill (born 1848) and John William Edgill (born 1850). Sometime between John's birth and their next son, William's birth in April 1851 the small family had moved to Cheetham, Lancashire, where William had taken up a new post as an accountant's clerk. Leaving Tom behind in Sheffield (perhaps while the family got settled in their new city) William, Elizabeth and John were living at 9 Southall Street, Cheetham with an Irish house servant by the name of Catherine Macguire.

Just 4 short weeks after the census was taken, Elizabeth gave birth to their third child; another son, by the name of William. Within the following 10 years Elizabeth was kept busy, with a further 5 births; John Ashley (born 1853), Mary Jane (born 1855), Harriett (born 1856), Elizabeth (born 1858), and Harry Rawson (born 1860). William was kept equally busy earning the income to keep them all fed, clothed, and housed in the manner to which they must have become accustomed. By the time of the 1861 census the family of 10 (2 parents, and 8 children) were living on Queen's Terrace, Withington Road, Moss Side, and employed 1 servant. William was no longer an accountants clerk, but was now 'clerk to the guardians'.

|

| The Chorlton Union was built in 1854-55 |

'The Guardians' were the guardians of the Chorlton Poor Law Union; the workhouse for the 12 parishes of Ardwick, Burnage, Chorlton-upon-Medlock, Chorlton with Hardy, Didsbury, Gorton, Hulme, Levenshulme, Moss Side, Rusholme, Stretford, and Withington. The area that the Chorlton Union covered would now be considered part of south Manchester. Each poor law union in the country appointed 19 guardians to oversee the workhouse, and it's activities. As the 'clerk to the guardians' William Nicholson Edgill would have enjoyed a degree of prestige.

In the following 10 years William and Elizabeth had a further 2 children; Charlotte Justina (born 1862) and Jessica Frances (sometimes recorded as Frances; born 1865), and in just one more year his wife, had died. Elizabeth Hague died on 6th July 1872, and William registered the death. She had died of tuberculosis- a disease that was to claim many more members of the Edgill family. On Elizabeth's death record he noted his occupation as 'Clerk to the Board of Guardians and Superintendent Registrar, Chorlton Union'. He wasted no time in remarrying, but did so not in Manchester, but at the Liverpool Registry Office, on the 10th September 1872; just 5 weeks after Elizabeth had died.

William's new wife was Hannah Standring; the daughter of James Standring, the omnibus proprietor from a previous blog piece. I have been unable to ascertain where Hannah was living in the 1871 census but I suspect she was residing with her brother James Massey Standring, who lived in Toxteth, Liverpool around that time. William Nicholson Edgill knew the Standring family reasonably well. In the 1861 census James Standring (of the Standring Omnibus Company), Hannah Standring and other members of the family were living just a few doors down on Withington Road. William was also an investor in James' omnibus enterprise.

The census of 1881 records a larger Edgill family; one which raises some questions. I discussed these issues in the 'Step' week post. Apologies for any duplication but it would be easier to explain things again here, although you're welcome to pop over via the embedded link, and read that post. In 1881, just 9 years after Hannah and William married, several children appear who should have been recorded in the previous census; Nanna Nicholson (born 1865), Florence Nicholson (born 1867), and Etholwyn Nicholson (born 1869). Their birth records have not been found. Only their baptisms, which took place years after Hannah and William were married, as adults, can be found. Their baptismal records give birth dates, and their given birth years match with later census records. As a result it is not possible to establish the parentage of these children. Is their mother Hannah, or Elizabeth? Is their father William Nicholson Edgill, or someone else? Or were they adopted? So many questions, to which we'll never have the answer! Another child was born in July 1871; William Nicholson Edgill (junior). The 1871 Census was taken in April of that year, so we should not expect to see a July baby in that census. His mother could well have been Elizabeth Hague, although it seems unlikely that a 50 year old woman suffering from the symptoms of final stage of tuberculosis would conceive. Not impossible, but highly unlikely.

Nevertheless, in the 1881 census we see those 4 extra children, plus three more children, born after Hannah and William's marriage; James Standring Nicholson (born 1874), Mary Beatrice (born 1875), and Agnes Hilda Violet (born 1880). Living then at 77 Cecil Street, Chorlton Upon Medlock, William was Superintendent Registrar and Clerk to the Guardians, with wife Hannah, sister Jane, and his children Elizabeth, Harry, Charlotte, Frances, Nanna, Florence, Etholwyn, James, Mary, and Agnes, plus a servant named Elizabeth White, from Nottinghamshire. William's eldest son Tom had died in 1877 whilst working overseas, and William, his third born son, and Mary Jane, his first daughter, had both died from tuberculosis, in 1879. Joseph Ashley (who had been a warehouseman in the 1871 census) was married in 1876, and was working as a salesman in 1881. Similarly, Harriett had married in 1878, and was a mother to two daughters by 1881.

.jpg) |

| The Ormond Building, as it looks today. In 1883 it would have looked pretty much the same. |

It was around the same time that the Chorlton Poor Union was growing and in need of new offices. In 1880 and '81 the Offices of the Poor Law Union was built on the corner of Ormond and Cavendish Street, and across from Grosvenor Square in Chorlton. The building was to be an imposing, grand structure, boasting about 100ft of street frontage. The architect noted that...

'To the left of the principal entrance first described, after passing through the vestibule, which will have glass doors, will be Mr Edgill's office, with an ante-room adjoining to a passage communicating therefrom to the registrar's offices, which will be of ample size, with a large-sized fire-proof room for the storage of books and documents, and with a private room, also immediately adjoining the registrar's office, which will be used principally for the registration of marriages; a waiting-room on the right of the principal lobby, adjoining to the porter's room, will be used by persons waiting to see the officials upon that business.'

It is related to this new office of Mr Edgill, that my favourite discovery, the Newspaper Clipping, pertains. On Saturday 14th April, the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser reported on a court case against the clerk to the Chorlton Guardians, regarding armorial bearings. An 'armorial bearing' was not defined by law, but could be described in laymen's terms as a coat of arms, or a design that related to heraldry. The displaying of armorial bearings was taxed, and required an excise licence from 1870-1944. (Prior to 1870 armorial bearings had been taxed in various different ways from 1798.) In this court case William Nicholson Edgill had been summoned to the court by the local excise officer, John Sinter. Mr Sinter testified that he had seen armorial bearings displayed in the windows of Mr Edgills offices at the Ormond/Cavendish Street Chorlton Union building, the previous December. He described the armorial bearings as one including a lion rampant, and another including the head of an ox.

|

| A lion rampant is a common symbol on heraldic crests. |

James Howard Ryder, a member of the Board of Guardians, gave witness to seeing the armorial bearings in the windows of the clerk's office. He stated that he had brought the board's attention to the matter, and that he had heard Mr Edgill admit that he had 'placed the crests in the windows without the sanction of the board' and that they were 'put into the windows without the authority of the guardians or the sanction of the building committee.' He confirmed that the guardians did not pay duty for the bearings.

The court heard that there were three armorial bearings on display in the windows; one to represent Mr Edgill's own family, another to represent his first wife's family, and the third to represent his second wife's family. The defence argued that Mr Edgill should not be paying duty on another person's window, despite the evidence that the guardians had not placed the crests in the window in the first place. The judge hearing the case advised that 'the guardians ought to tell Mr Edgill to take the crests out of the windows.' The case was dismissed.

|

| Click here to see a full transcript of the newspaper article. |

It seems that Mr Edgill was perhaps using the opportunity to display personal crests in his office windows, thereby evading the tax that should have been payable. Furthermore, after having researched William Nicholson Edgill, and his family, including his two wives, I would argue that none of them had family crests to display in the first place! The case is a wonderful snippet of this ancestors character which I feel portrays him as a pompous man who has come up in the world, from the son of a mason to a reasonably well off man, who was actually still a clerk. Living in the industrial world, where 'new money' was on the rise, but without the power and wealth of 'new money', I suppose Mr Edgill was reaching for some 'old money' status. At the same time, William Nicholson Edgill went for the cheap route, which in the end, made him look a bit foolish.

The old Chorlton Union building still stands, and is now a part of the Manchester University school of art. I have reached out to the people there, to ask if there are any armorial crests still in the windows there, but they assure me that the windows were replaced for modern ones long ago.

William Nicholson Edgill lived until he was 70 years old, and worked as the clerk to the Chorlton Union guardians, and superintendent registrar right up to his last. He died from a fatty degeneration of the heart and kidneys, and albuminuria (a sign of kidney disease.) Medical friends have suggested that this might have been due to an excess of alcohol consumption in his general lifestyle. If this is true, this gives me another clue as to his character.

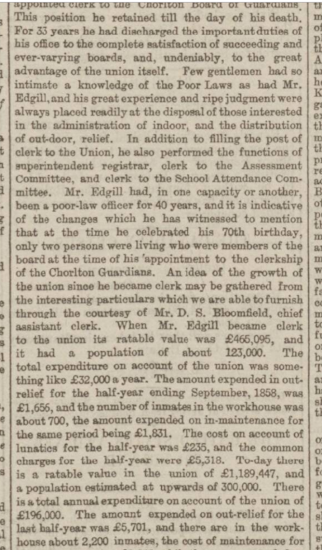

William Nicholson Edgills obituary was very thorough and we can learn a lot about him in his professional life. His funeral was also well covered by the papers at the time, and his daughter Florence wrote a letter to the board of guardians, which was read at their meeting, following Mr Edgill's death. All of these, of course neglected to refer to the armorial bearings case!

|

| The obituary for William Nicholson Edgill, clerk to the Chorlton guardians and superintendent registrar, 1821-1891. |

Whilst we can never really know what our ancestors were like, its only with these sorts of snippets that we can get a glimpse of their character. Whenever we research an ancestor, we must do a search through newspaper archives; you never know what you might find!

*******************************************

https://www.officemuseum.com/office_workers.htm

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/147827294.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chorlton_Poor_Law_Union

https://manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk/buildings/chorlton-poor-law-guardians-offices-ormond-street-cavendish-street-all-saints?fbclid=IwY2xjawEothtleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHWl34RYOydLt4oqn-Ou3OunS_J4oSk3okDbavDOT3lb6ywI60xx1y_mw6w_aem_Zr1wlSt6QXIkS84kygr4GA

https://modernmooch.com/2018/12/05/all-saints-grosvenor-square-manchester/

https://friendsofsheffieldcastle.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Castle-Hill-M-Clark.pdf

https://ifthosewallscouldtalk.wordpress.com/2017/02/02/hidden-histories-2-union-street-manchester-buildings-of-the-northern-quarter-part-2/

https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/tuberculosis-a-fashionable-disease/

No comments:

Post a Comment