Most of my ancestors were working class people, working jobs that were rife with dangers that would have health and safety managers' heads spinning today. Miners working in cramped conditions where mine shafts could collapse, and where the only person responsible for keeping the air breathable was a small child sitting alone in the dark, goodness only knows how many metres under ground. Laundresses working with all sorts of chemicals, soaps, and hot water to get all the stains out, and then using dangerous machinery to wring the laundry dry. And men, women, and children working in factories and mills where massive machinery could pull them in and devour them in an instant of forgetfulness. So many of my ancestors were working hard, dangerous jobs, in poor conditions, and on a diet of poor nutrition and often living in sub par sanitary conditions.

Without any medical records it's hard to know exactly how our ancestors were affected by the poor working, and living conditions they endured. In truth the only medical records we have for our ancestors are their birth and death certificates, and the occasional inquest report.

The ancestor that I will be writing about this week was my 3x great grandfather; Henry Vinall. He was the son of John Vinall and Charlotte Mitchel, and was born in Henfield, Sussex in 1813. In April 1838 Henry Vinall married Jane Munro in Brighton, Sussex, and they settled into her family home at 3 St Peter's Street. Jane Munro, like her mother, and most women in her family both past, present and future, was a laundress. Henry Vinall was a painter.

Paint in the Victoria era was quite a different affair, to the paint we use today. In the early Victoria era paint was hand mixed, which made colour matching very difficult. Painters would use a dry pigment and grind it into a paste, adding turpentine and oil to make it into a liquid that could be brushed onto walls etc. The oil gave the paint its lovely glossy finish that we so often consider an integral part of the Victorian aesthetic. It was down to the skill of the painter, to complete the work without leaving brush strokes. For exquisitely glossy finishes the painter would wait for the paint to dry, sand it down with a pumice stone, and then repaint it, perhaps up to 10 times.

Instead of wall paper, stencils were often used to create patterns and designs on the walls, and floors would be painted to resemble rugs. Paint was also used to create effects like marbling or graining. Common and relatively cheap slate would be painted in such a way as to make it resemble marble, and simple wood trim could be painted to look like expensive oak or walnut.

|

One of the most popular colours of the Victorian era was green, or more specifically Scheele's Green. Carl Wilhelm Scheele was a Swedish chemist who invented a brilliant green pigment by blending copper and oxygen with arsenic. Scheele's Green was absolutely what all the Victorians wanted in terms of fashion and design, not just in their homes, but on their bodies.

Arsenic was well known as a poison in Victorian times. It could be easily bought at the local chemist, to be used as rat poison, and if you're a fan of historical murder mysteries, you'll be familiar with the use of arsenic for more nefarious means. However, Victorians believed, at first, that they would have to ingest the pigment, to suffer a toxic reaction to the arsenic. The poisonous green was used to create green paint, green wallpaper, and green fabric. Fashionable women wore green dresses, and green upholstery and curtain fabric would grace the furniture and windows of their homes. As long as they didn't lick the walls, curtains, or clothes, they thought they would be just fine. After the success of Scheele's Green, chemists and painters experimented with arsenic by adding it to other pigments, to create canary yellows for example. Of course, it didn't take them too long to realise how dangerous this pigment was. Workers in the factories where the wallpaper, paint, and fabrics were made started to get very sick. Seamstresses, upholsterers, and painters and decorators working with these poisonous materials, started to get very sick. But nothing really changed until the rich started to get sick and die. It wasn't until the late 1860s that doctors made the connection between the strange maladies, and deaths that had occurred, with the poisonous green pigment. Finally the desire for green had started to ebb, as people became more aware of the dangers of Scheele's Green. Green became a terribly unpopular colour as a result, and even today it is considered an unlucky colour in the world of high fashion. By the late 1890s the British government started to tighten up the rules about how arsenic and other poisons could be used in manufacturing; too late to be helpful to our Henry Vinall, who died in 1897.

|

| In Front of the Mirror, by Georg Friedrich Kersting, 1827 |

|

| Many Victorian women's make up products would contain lead which helped them achieve the pale complexion that was all the rage. |

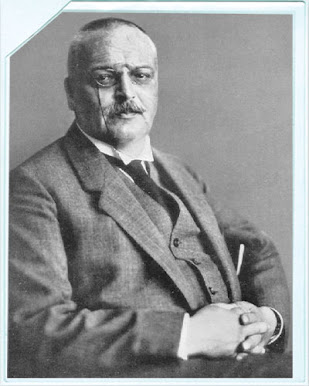

Considering the work that Henry Vinall did throughout his lifetime, and the risk of such work, the impact that painting in the Victorian era could have on his cognitive skills, and the mention of 'senile decay' on his death certificate, I have wondered at whether his mental decline could have been caused by his work with dangerous chemicals in the paints he used. Of course, he could have naturally developed a neurocognitive disorder, to use a term doctors would use today. It wasn't until the early 1900s that Alois Alzheimmer identified the characteristics of progressive dementia, and from that point science and medicine have developed a far better understanding of neurodegenerative diseases, with still so much more to understand and learn how to treat. The Alzheimer Society of Canada is a charity that works to support those affected by Alzheimers and other neurocognitive disorders related to age. It also raises funds to support those who study and research that area of medicine. If you are would like to make a donation, or seek support you can find them here.

|

| Alois Alzheimer, 1864 - 1915 |

Henry Vinall died in his home at 4 St Peter's Street, Brighton; the home where he had lived with his wife Jane Munro for almost 60 years, the home where he and his wife had raised 8 children and celebrated many grandchildren. He died with his daughter Louisa by his side, the youngest surviving daughter, who never married and was the constant carer for the family. In Henry's life time the world witnessed, amongst other things) the publishing of Jane Austen's book "Pride and Prejudice", the invention of the flintlock revolver, Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, the publication of Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein", the opening of Cadbury's first chocolate shop, the invention of electricity, massive electoral changes in England following the Great Reform Act, the abolition of slavery in all countries of the British Empire, the coming to the throne of Queen Victoria, the publication of Dickens' "A Christmas Carol", the Crimean War, the construction of the Suez Canal, the publication of Charles Darwin's "The Origin of the Species", the opening of the first part of the London Underground, Pasteur's invention of a rabies vaccination, the invention of basketball, and the gramophone record, and in 1896, the revival of the Olympic Games. He died at the age of 84 on the 25th July, 1897.

#Edgill

https://www.adrianflux.co.uk/victorian-homes/victorian-interior-painting/#:~:text=The%20Victorian%20era%20was%20now%20filled%20with%20magnificent%20colour&text=However%2C%20the%20Victorians%20were%20still,distemper%20was%20saved%20for%20ceilings.

https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/features/scheeles-green

https://www.slam.org/blog/arsenic-in-victorian-wallpaper/#:~:text=Chemists%20and%20paint%20makers%20introduced,that%20arsenical%20wallpaper%20could%20kill.

https://underthemoonlight.ca/2017/11/04/the-long-history-lead-white-paint/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lead_poisoning

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1467-9566.12452

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dementia#History

https://www.carehome.co.uk/advice/a-brief-history-of-dementia

https://alzheimer.ca/en

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_19th_century

https://www.ranker.com/list/harmful-victorian-household-objects/amandasedlakhevener

https://www.pubhist.com/w11645

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)