Over recent blog posts I have described the lives of my great grandfather, William Nicholson Edgill, and his three older siblings, Nanna Nicholson Edgill, Florence Nicholson Edgill, and Etholwyn Nicholson Edgill. I have always been intrigued by these four siblings, as I have never been able to find any birth records for the four of them, and they were all baptised as adults at the age of 17 (Nanna & Etholwyn), and 15 (Florence & William). I've also been completely unable to find any of them in the 1871 census, nor their 'mother' Hannah Standring. The four of them just seemed to appear out of thin air, after Hannah and William's marriage, in September 1872, and in the 1881 census. Where were they all in 1871, and who really were their birth parents?

Some other amateur genealogists on Ancestry have decided that Elizabeth Hague, William Nicholson Edgill's first wife, was the mother of the children; I think soley because she was his wife at the time. To explain the mystery a little better I think it's best that I write this post in the form of an outline of William Nicholson Edgill and his family life. (His professional life was also VERY interesting, but that can wait for a different blog post!) In an effort to make things as simple as possible I shall refer to William Nicholson Edgill, the father, as William Nicholson senior, and William Nicholson Edgill, the son, as William Nicholson junior.

William Nicholson Edgill (senior) was born in Sheffield, in 1821. He married Elizabeth Hague in 1846, in Sheffield, when he was working as a merchant's clerk. William and Elizabeth had a total of 10 children together. Their first two children were born while the family were still living in Sheffield; Tom Nicholson born in 1848, and John William born in 1850. When the 1851 census was taken William Nicholson (senior) was recorded as working as an accountancy clerk, in Manchester.

|

| 1851 Census- Southall Street is a road that now runs the edge of HM Prison Strangeways |

Later in 1851 they welcomed their third child, another boy, named William, born at the same address in Cheetham, Lancashire. In the following seven years the couple had 3 more children; Joseph Ashley (1853), Mary Jane (1855), and Harriett (1856). In 1858 William Nicholson (senior) took the post of clerk to the Guardians at the Chorlton Poor Law Union, and their daughter Elizabeth was born. Another son, Harry Rawson was born in 1860, and the 1861 census shows the family of 10 (2 parents and 8 children) all living together on Queens Terrace, Withington Road, Moss Side.

|

| 1861 Census- an additional maid in the household suggests a certain level of wealth |

In the same census, just down the road, at Marlborough Place, Withington Road, Moss Side Hannah Standring (his future second wife) was living with her widowed father, siblings, and 3 year old cousin. The last two children that I am certain were birthed by Elizabeth were Charlotte Justina, born in 1862, and Jessica Francis, born in 1865.

Elizabeth was 44 years old (close to the end of her child bearing years) when Jessica was born, on the 27th February 1865. The oldest of the 4 'mystery' siblings, Nanna, was born on the 10th May, 1865. It seems clear that based on these two close, but not close enough for twins, birth dates Elizabeth could not possibly be Nanna's mother. The other three siblings were born in 1867 (Florence), 1869 (Etholwyn), and in July 1871 (William Nicholson junior).

In the 1871 census Elizabeth Hague was living with her ten children, and a servant, by the name of Ann Thompson. William, her husband was not at home, at that time. He was visiting his dad in Sheffield. This does not signal that something nefarious or illicit was going on. The census recorded anyone staying at the home on that day/night. William was most likely simply visiting his father, John Edgill, who was 80 years old at the time the census was taken. What is frustrating however, is that I've found it impossible to find Hannah Standring, William's second wife, and 3 of the 4 children in question at all in 1871. (The census was taken in April 1871, and William Nicholson junior wasn't born till July 1871.) A decade before, in 1861, Hannah was down the road, and in 1871 she had apparently disappeared! The 3 children seem to have not existed officially until the 1881 census!

|

| 1871 Census- note son John was working as assistant clerk to his father |

Elizabeth Hague died the following year, from tuberculosis, on the 6th July, 1872. She could have been the mother of my great great grandfather William Nicholson junior. She was alive at the time. But she was 50 years old, and possibly sick with tuberculosis which would later claim her life. She also already had a child named William, and it seems unlikely that the parents would use the same name twice, when the older brother was still living.

Just 2 months after Elizabeth's pasing, on the 10th September 1872, William Nicholson Edgill (senior) married Hannah Standring at the Liverpool register office. Such a swift second marriage of a husband, after a wife's death was not uncommon at the time, especially when there were so many children for whom to be cared. But it is interesting to me that they were married in Liverpool, and not somewhere in the Manchester area. As the superintendent registrar for Chorlton he could have easily arranged for them to be married locally. Perhaps there was a desire to keep the marriage quiet....? Of course, we can't know their reason, but it sure is frustrating not knowing!

In the following census of 1881 the large blended family were recorded as living together, with a few missing people. This is the first time that we see the 4 siblings in question recorded; finally they officially exist! Along with William senior and his new wife Hannah we see 4 of Elizabeth's children still in the home; Elizabeth, Harry, Charlotte, and Francis.

|

| 1881 Census |

Since Elizabeth's death the family had experienced a series of tragic losses. Tom Nicholson Edgill had left England and gone to work in Sierra Leone as a mercantile clerk. The adventure to Africa came to an abrupt end when the bachelor died in 1877, in Madeira. William Edgill (the son born to Elizabeth Hague in 1851) and sister Mary Jane both died in 1879; more victims of tuberculosis. William died in April, and Mary in July. It must have been a tragically hard year for the family.

|

| Phthisis Pulmonaris was the medical term used then, for pulmonary tuberculosis. |

|

| I believe that Mary died in the home where her sister Harriet lived with farmer husband, Peter Fletcher. It would be common in Victorian times, for the affluent, sickened by TB, or consumption, to seek cleaner, country air. A family farm would be the perfect escape from city air. |

Over the years there had also been reasons for celebration, with marriages, and the births of more children and grandchildren for William Nicholson Edgill senior. In 1876 Joseph Ashley Edgill married Mary Bamford, a school mistress, and daughter of a glass manufacturer, William Bamford. By the time of the 1881 census Joseph Ashley was living at 1 Thurloe Street, Rusholme, just south of the family's neighbourhood of Chorlton on Medlock, with his wife Mary, and son William Bamford Edgill.

John William Edgill married a Scottish lass, named Elizabeth. In the 1881 census they were living together, with their daughter Amy Elizabeth, an Irish servant by the name of Bridget Read, and a boarder, and possibly a relative of step mother Hannah, called Edward Standring.

Harriett Edgill married a farmer named Peter Fletcher in 1878, in Hulme, Manchester. His farmland was in Woodhouses, Dunham Massey. By the time of the 1881 census they had two daughters together; Jessica, and Ann Catherine.

William and Hannah had also been busy in the years since their marriage. Three new children were born to them in those 9 years; James Standring Nicholson Edgill, born in 1874, Mary Beatrice Edgill, born in 1875, and finally baby Agnes Hilda Violet Edgill, born in 1880.

The 1881 Census also recorded, living with William Nicholson senior, and wife Hannah these 4 new children;

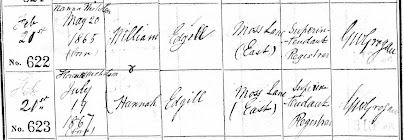

Nanna Nicholson Edgill, born in 1865, in Bowdon, Cheshire

Florence Nicholson Edgill, born in 1867, in Liverpool, Lancashire

Etholwyn Nicholson Edgill, born in 1869, in Stockport, Cheshire

William Nicholson Edgill, born in 1871, in Romiley, Cheshire.

|

I believe that it was here, at Rose Bank, Gibraltar Lane, that William Nicholson Edgill junior, was born, or spent his first few years. Further down the lane, behind the photographer, was a row of mill worker cottages, and the Gibraltar Mill. In later census reports William gave 'Gibraltar, Cheshire', as his place of birth. And directory entries for his father gave the address of Rose Bank, Haughton Dale, which is where the Gibraltar Mill was situated. It's fun to imagine that these children might have been ancestors.

|

I find it so curious that these children all have such different places of birth. If they were Hannah's children, she must have moved around a lot in just 6 years! If they were Elizabeth's children, where were they all in 1871? Since we know that Elizabeth had tuberculosis, which can be transmitted to a fetus in utero, could they have been born sickly, and were sent as babies, to be cared for in cleaner air than that afforded to them in Chorlton? If that was the case, I should still have been able to find them in census records.

An alternative theory is related somewhat to William Nicholson senior's job. He worked as a clerk to the Guardians of the Chorlton Union; the workhouse. In this role William would have been well aware of the needs of the people depending on the poor law union's facilities. He would also have been aware, and perhaps involved in the various work that the union was doing to improve those facilities, and other charitable works being carried out in the Manchester area. There was a great need to support orphaned children in Manchester at this time, as was common throughout England. This was an era of dangerous industrial work, where a lack of health and safety in the workplace was commonplace. It was also a 'pre penicillin' time, and an era where vaccinations were uncommon. Diseases such as the measles, scarlet fever, and tuberculosis were so common and deadly, leaving a large number of children orphaned and in need of care by whatever means society could offer. The charitable people of Manchester were active in their efforts to help these children. In 1854 a group of Manchester businessmen founded a school for the orphaned children of warehousemen and clerks, called "The Manchester District Schools for Orphans and Necessitous Children of Warehousemen and Clerks". The school was (and still is) located in Cheadle Hulme. Warehousemen and clerks in the city were invited to pay a small subscription, and in return their children were promised care, shelter, and an education, even if they were orphaned. The orphans attending the school slept in dormitories at the school, whilst fee paying students whose parents still lived, attended as day students.

|

| The school is now an independent (private) school, and was renamed Cheadle Hulme School. |

Meanwhile in Chorlton, the board of Guardians recognised that there was a need for child specific housing, and in 1880 developed a children's orphanage and school across the road from the workhouse, which housed at least 271 children of school age, plus 70 infants.

Considering William Nicholson senior's job as a clerk, and the number of children he had who also became clerks, and spent time working as warehousemen, it occurred to me that he could have had a connection to the school. Perhaps he paid a subscription so he could be confident that his many children would be cared for, if he died before they were all of age. It also occurred to me that in his work at Chorlton Union he and Hannah may have decided to move their charitable acts into the family home, and adopted the 4 children. This would conveniently explain their various birth places, since they could potentially have different birth parents. There is no way of telling if they had adopted Nanna, Florence, Etholwyn, and William junior. Adoption records were not kept at that time, and was done on purely an informal arrangement.

Sadly, the baby of the family Agnes Hilda Violet had died, aged 2, of scarlet fever in 1882. I have not been able to find any record of her ever having been baptised, which, if she was not, was uncommon for the time. Interestingly, the only record we have that suggests the birth dates of the 4 siblings in question, are their baptismal records, all of which happened after Agnes' death. They were baptised in pairs, as teenagers, with Nanna and Florence being baptised together, in 1883, and Etholwyn and William junior being baptised in 1887. I have wondered at these late baptisms, and have pondered on whether they were a reaction to the unbaptised baby's death.

Whilst it's clear that Hannah Standring was step-mother to the older children in the family, born to Elizabeth Hague, the records suggest that she cared for her step children, and they for her. In the death certificate for William (Elizabeth's son; see above), Hannah was named as the person who registered the death; she was present at his passing, and was recorded as 'mother'. After her husband William Nicholson senior's death in March 1891, Hannah continued to ensure all her children (step, birth, and possibly adopted) had a safe home in which to reside. In the 1891 census, taken the following month, adults Harry, Charlotte and Francis were living in the family home at Brunswick Lodge, 404 Moss Lane East, along with their step/adopted siblings Florence, Etholwyn, and William, and half siblings James and Mary Beatrice.

|

| 1891 Census- The census was taken roughly 10 days after William Nicholson senior's death. Note that son Harry was working as the interim Superintendent Registrar, because it was so soon after his death that the board of guardians hadn't yet found a replacement for the position. |

In ensuing census reports we see Hannah continuing to live with the children of her blended family. Sometime between the 1891 and 1901 censuses the family, somewhat reduced in size, moved from the large house on Moss Lane East, to a smaller terraced house on Sandy Lane, Chorlton-cum-Hardy. William Nicholson junior (my great grandfather) had moved to London, by this time, and was working and living in the hotel/restaurant/brothel 'The Golden Bells'. Harry Rawson Edgill (Elizabeth Hague's youngest son) sadly died in 1894; yet another tuberculosis victim.

|

| Brunswick Lodge, 404 Moss Lane East, was the family home at the time of William's passing. It is now the Jaffaria Islamic Centre. (I have no idea who the man in the portrait photo was. He may have been an ancestor, or someone who lived in the house, after our ancestors moved out.) |

Hannah lived on Sandy Lane, until her death, with step daughter Charlotte, possibly adopted daughter Florence, and daughter Mary Beatrice. She was named as head of the household in both 1901 and 1911, but in 1921 her daughter Mary Beatrice was named as head. I'm not sure if this is because the deeds of the house had been handed over to Mary, perhaps in an effort to escape any death duty, or if Hannah, in her late age, had lost the mental capacity to manage her own affairs. Either way, it does seem that, in her senior years, Hannah was being looked after by her step daughter Charlotte and her daughter Mary.

|

| Manchester Evening News, Saturday August 6th, 1927 |

Mary Beatrice married widower Frederick William Bates, a pharmacist, in 1925, and Hannah moved with her daughter, into their marital home at 2 Wellington Crescent, Darley Park, Stretford, Manchester. It was here that the mother to so many children in her large blended family, Hannah Standring died, at the grand old age of 90, in 1927.

Whether Hannah was a birth mother, adoptive mother, or step mother, perhaps isn't important. What is clear from the footprints she's left behind, in the records of her life, is that she was a mother.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)