According to findmypast.co.uk there are 7 different types of surnames (last or family names.) Our last names might be linked to an ancestor's parent's first name (such as Robertson, or McRobbie, Madison or Marriott), or an ancestor's occupation (like Carpenter, or Taylor). Other last names might relate to the place where an ancestor used to live (as in Essex, or London,) and some (especially those who are descended from the gentry or royalty) might be named for the estate which their ancestor owned (like Windsor for the royal family.) Some in our family have theorised that the family name 'Grosset' is an old French Characteristic Surname, and comes from an ancestor with a large head; 'grosse tête'. This is presumably what a few French people might have thought when we gave our name to book a table in a restaurant, or checked in at a campsite, whilst on holiday in France. It would at least explain their giggles and smirks! Recently a fellow Grosset and distant cousin of my husband suggested that it could be a Geographic Name, related to the old Scots word for gooseberry. Perhaps an ancestor lived near a gooseberry patch, or farmed gooseberries. Scotland's national poet Robert Burns, in his poem Tae a Louse, compares the louse he sees on a fancy lady's bonnet at church one Sunday to a gooseberry, which he refers to in his light Scots dialect as a 'grozet';

"My sooth! right bauld ye set your nose ou

As plump an' grey as onie grozet:"

"My sooth! right bold you set your nose out,

As plump and gray as any gooseberry:"

The same distant cousin also mused that perhaps the name was actually a characteristic name, and the ancestor was small, hairy, and had a greenish skin tone!

Over the generations the spelling of the name Grosset has changed somewhat, and this gives us an idea of how the name was pronounced in previous times. Below gives an idea of where the family was, what work they were doing at what time in history, and how the name was spelled and potentially pronounced in that era.

Grosset - Gosart - Grozard

The Grossets of the 1800s were based in Midlothian, Scotland. They were found in Portobello and Duddingston, Midlothian during the Industrial era, presumably attracted to the heart of industry for better wages, and consistent work. Some were blacksmiths, others glassblowers in bottle factories, and there were coal miners and railway workers too.

|

| This Robert Morden map, dated 1703, shows the south east of Scotland. The location of Portobello is circled in red. |

Previously, however, they were found in more rural areas south of Edinburgh, including Temple, Middleton, and Borthwick, Midlothian, where they worked at farms as ploughmen and farmhands. They remained in this area throughout the 1700-1800s.

|

| This same map shows the location of Borthwick circled in blue. Temple and Middleton are in roughly the same area. |

Prior to the 1700s the family were located in Eddlestone, and Peebles, in Peeblesshire, considered a part of the border country of Scotland, known in earlier times as the Middle Marches.

It seems like the name certainly had a harsher /z/ sound than the soft /s/ that we use today. And the final syllable in the name was possibly said without the clear /t/ that we use to complete our name today.

The earliest Grosset ancestor I can reliably trace is Thomas Groser, born 1655, in Peebles. He married Margaret Irvine, born 1657 in Eddleston, Peeblesshire. Her father was Archbald Irvin, born 1630 in Peebles. The Irvines/Irvins were a Scottish Border Reiver clan, and it's possible that the early Grossets were actually part of another Border Reiver clan named Crozier.

|

| The Crozier motto "Crux Enim Clavis" means "The Cross is the Key". |

The Border Reivers were a group of families whose home lands straddled the border of England and Scotland. The border was split into Scottish East, West, and Middle Marches, and English East, West, and Middles Marches. This land was wild, and fiercely fought over by both the English and Scots. People who lived in this part of the country were not easily able to grow crops partly due to the land not being ideal for crop growing and partly due to the frequency of the land becoming a battle ground. Who wanted to invest in growing a crop when that said crop could be trampled on or burned down in battle? Instead the families of the border country dealt in livestock, but rarely their own. To reive is an historic Scottish word, meaning to carry out raids in order to plunder cattle or other goods. The reiving families, when the larder was bare, would put on their armour, raid a nearby farm and take what they needed. The typical reiver life did not stop at raiding and plundering for livestock. Allegiances were only good for as long as the reiver family felt they benefitted from it, and they were known to fight, for either the English or the Scots, depending on how well it suited them at the time, and no matter which side of the border they lived. There were even instances when, if the side they were fighting for was losing a battle, they would switch sides right there in the middle of the battle. These were a fierce people who were not to be trifled with; their existence and way of life brought to our language the words 'bereaved' and 'blackmail' (greenmail was the amount you paid for your rent, whilst blackmail was what you paid for protection.)

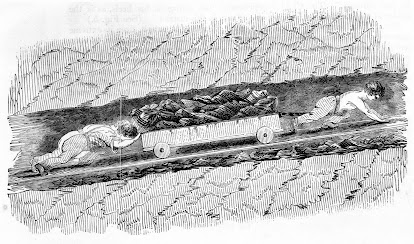

|

| Reivers at Golnockie Tower, a 19th century print features a pele/peel tower in the centre. |

"The Armstrongs were the most feared and dangerous riding clan on the whole frontier.... In Johnnie Armstrong's day they could put 3,000 men in the saddle and probably did more damage by foray than any other two families combined, both in England and Scotland"

The Croziers were aligned with a powerful family, and with that power the Croziers would have found security, and danger in equal measure.

The era of turmoil in the bad lands of the border countries was to come to an end when England and Scotland were united after the death of Elizabeth I, the queen of England. After her passing, James VI of Scotland took the thrones of both countries, unifying them and creating the union of Great Britain. The border was in effect, no more, and King James took no time in resolving the problems with the border people. He ordered that the border lands should be pacified, and thus it was so.

|

| James VI of Scotland & James I of England |

Reiver families were rounded up, and lands were confiscated. The Armstrongs, amongst other clans that had proved to work against both the Scottish and English crowns in the past, were deported to Ireland. A large Armstrong population settled in Country Fermanagh, Ireland. Armstrong is in the top 50 most common last names in Ulster today. Other reiving families were encouraged to serve as mercenaries in wars further afield. And others turned to the plough and worked the land, much like our early Grosset ancestor, Thomas Groser (born 1655).

Many of the most feared reiver clans were executed without trial, as was the chief of the Armstrong clan, Archibald Armstrong of Mangerton, who was hanged around 1610. It did not escape my notice that the name of the chief of one of the most feared reiver clans, with whom the Croziers were connected, was an Archibald, as was the name of the father of Margaret Irivine (born 1657); Archbald Irvin (born 1630).

|

| Mangerton Tower, the home of the Armstrongs, was destroyed, and Archibald Amrstrong, the clan chief, was executed. |

In "The History of Liddesdale, Eskdale, Ewesdale, Wauchopedale, and the Debateable Land" by Robert Bruce Armstrong (published by David Douglas in 1883), the author described all the clans who lived in the Scottish Middle March. In the Liddesdale area, in 1376, we can see an area where people named Croyser were paying rent to the lord of the time.

Other mentions are made of the Croyser/Crozier clan in the aforementioned book, including a reference to a family home at Riccarton;

"During the sixteenth century the Crosars occupied lands in Upper Liddesdale..... the family of most consequence lived at Riccarton, where (near a burn of the same name) some remains of a tower may still be seen."

|

| All that remains of Riccarton tower. |

In his notes Robert Bruce Armstrong also mentioned that Huddishouse was also a home to the Croziers. He went on to note that an ancient account had reported that "The only peel house that remains entire is Hudshouse. The vault is immensely strong and has double doors bolted on the inside." Sadly, like most of the pele towers that were a common design of home for the border country, it has long since disappeared.

Both Hudshouse and Riccarton are a little south from Peebles and Eddlestone; certainly a days ride and no more. It is quite possible that a reiver family, escaping the destruction of their family home and way of life should ride a day north to start a new life. Reivers were well known for their horsemanship and were used to riding long distances for their raids. Why not make the same sort of journey to start again?

|

| Riccarton and Hudshouse are circled in red. There were two Riccartons, Over (upstream) and Nether (downstream). It seems likely that the Croziers were located at Nether Riccarton. |

It is easy to see how the name Crozier might mutate to Grosset. The letters C and G could easily be poorly written and mistaken one for the other. There is also the pronunciation of the two letters that make a close similarity. The sound /k/ is the same sound as the sound /g/ with the exception of the former being unvoiced and the latter voiced. Try placing your hand gently on your throat. Say the the word 'cold', and then 'gold'. You should notice a difference in what you feel your vocal folds are doing when saying 'gold' as opposed to 'cold'.

|

| The Robert Morden map again, shows the location of Hudshouse and Riccarton, circled in pink. Here we can see the possible migration north, of the Grosers--> Grossets. |

Since I can't trace our family any further back than 1655, and I can't make a definite connection with the Croziers of the Scottish Middle Marches prior to 1655, we will have to accept that we will perhaps never know where our name comes from. My son, however, already fascinated by the border reiver connection from my side of the family (an English Middle March clan, by the name of Charlton), is super stoked and happy to fully lean in to the idea that he is a double reiver.

|

_________________________________________________________________

https://www.armstrongclan.info/clan-history.html

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofScotland/The-Border-Reivers/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Border_reivers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_Borders

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clan_Armstrong

https://clancrozier.com/crozier-distribuition/#:~:text=name%20is%20based%20on%20cross,Croyser%20that%20of%20hut%20builder.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peel_tower

https://reivers.info/riccarton-tower/

https://maps.nls.uk/view/00000398

https://electricscotland.com/webclans/atoc/clancrozier.pdf

https://books.google.ca/books/about/The_History_of_Liddesdale_Eskdale_Ewesda.html?id=nFr7oQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

https://www.stravaiging.com/history/castle/hudshouse-tower/

https://maps.nls.uk/view/216441416

.jpg)